Rites of Passage and Morocco’s Zayan Tribes

Issue 51

Jawad Al Tabba’i

PhD Student, College of Arts and Humanities, Sais, Fez

Rituals are inherited ways of performing religious and social ceremonies at events such as births, aqīqah (the Islamic tradition of sacrificing an animal on the occasion of a child's birth), circumcisions, weddings and deaths, or what are known as rites of passage. Socialisation plays a crucial role in preserving rituals in accordance with customs as part of identity; sometimes these rites turn into beliefs.

Rituals are often performed as a collective process during which the supernatural, symbols, and representations of good and evil are present. The belief that the person is exposed to the eye, magic, and sorcery increases and fear of the unknown grows, so all possible means are used to remove all sources of evil.

These rituals are similar in many respects but they differ in other aspects depending on the region. This geographical dimension helps us to identify what is unique about the rites of passage for the Tamazight tribes in Zayan in the Middle Atlas mountains and the central plateau, and to familiarise ourselves with the most prominent characteristics of each rite of passage in Zayan.

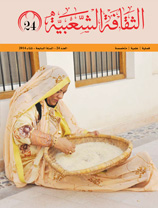

Henna is important in the rites of passage. People use henna as a disinfectant for newborns and on the seventh day after birth. Zayani women often coat their breasts with henna when weaning. To accelerate the healing of a person who has been circumcised, a group of people will apply henna that has been mixed in a large bowl.

The henna ceremony is the most important part of a wedding. In Morocco, people have ascribed magical superpowers to henna; it is believed to bring good fortune and protect brides from evil. Henna is also used in rituals when burying unmarried people who have died. If a widow applies henna after her husband’s death, it is a sign that ‘iddah’ (the period of waiting) has ended because the traditions of the region’s tribes almost forbid the use of henna during this period.

A powdered form of henna is used in the traditional medicines that are prescribed for several diseases, and drinking a blend of herbs including henna is believed to improve fertility and expel evil spirits. Henna is part of the rituals at peasants’ ceremonies and seasons, and in beliefs related to folk culture. For example, there is a belief that if an inverted henna bowl is found, or if henna is thrown into a dry well or buried in a grave, it will impede fertility. Placing henna in the reproductive system of a female donkey is believed to inspire hatred and animosity towards the person targeted.

People still believe that henna promotes hair growth, especially for women, if applied during the night during Ramadan. Ibn Hilal Al-Sajlamasi says, “There is no harm in applying it at the beginning of the night, and its strength diminishes… It is better to wash it before dawn.”

Henna remains a symbol of generosity and goodwill. In Zayani tribes, a woman will not leave her hostess’ home without applying henna to her own hands and feet.