A Word from the Editor Folk culture and the new generation

Issue 37

At the beginning of the 2008-2009 academic year, Professor Ahlam Al Amir from the Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Department visited the offices of the Folk Culture Centre for Studies, Research and Publishing. She wanted to explore the possibility of cooperating with the centre and adding folk culture studies to the syllabus in three phases. The first phase involved an experiment with a limited number of schools, the second involved adding more schools, and the third phase involved developing an educational curriculum that included folk culture for all schools.

We were very appreciative of the enthusiasm with which teachers reacted. We worked hard to make the experiment a success. Our collaboration was monitored by several experts from the Curriculum Department. We knew in advance that we would face challenges and obstacles, but once the administration made the decision, we were able to help. This issue’s ‘In the field’ includes a technical report about the last meeting between experts from both organisations and a description of the achievements.

A few days ago, we were pleased to learn that the Executive Council of the International Organization of Folk Art (IOV) had congratulated Bahrain’s Ministry of Education for successfully adding folk culture to the syllabus for secondary schools. This signifies that this is a significant educational achievement, and an example to be followed. This achievement has distinguished Bahrain among Gulf and Arab countries.

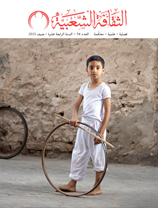

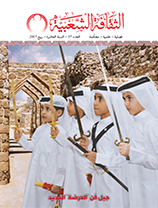

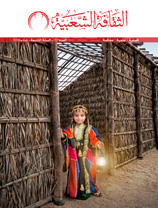

The Bahrain Ardah Society, (Ardah is a traditional dance), has organised theoretical and practical courses for children aged 8 to 13. This spectacular desert or Bedouin art was brought to Bahrain and the rest of the Arabian Gulf by Arab tribes who migrated from the centre of Najd and the outskirts of the Arabian Peninsula. Each region adapted the dance to fit its traditions. Initially, the dance was performed as a call to war, then it was performed at weddings and national celebrations attended by kings and dignitaries.

This dance has artistic features and traditions, and it involves the use of props such as traditional swords, guns, flags and several types of drums and tambourines. There are usually at least 100 participants, including tambourine and drum players, singers, gun carriers and sword dancers, and the latter are usually leaders, princes and kings.

Like folk songs, Ardah changes with each generation, and this affects the components of the dance and its emotional impact. These changes may distort the art form, because the musicians, composers and singers are growing very old and the new generation is losing its connection to this noble art. In order to attract the attention that this art form deserves, Bahrain’s Royal Court appointed Royal Court Minister Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmed Al Khalifa as the honorary president of the Ardah Society.

The Bahrain Ardah Society recently offered a training course for children to teach the new generation about the origins and ways of performing Ardah. This was an important step, although it came late. It is in line with the Ministry of Education’s initiative to introduce folk culture to the curricula in order to emphasise the value of national culture and the importance of its innovators and their sense of belonging to the nation.

Ali Abdullah Khalifa

Editor-in-Chief