Folk culture and tourism

Issue 25

With the prevailing trend towards diversifying sources of national income in Arab countries - especially oil-producing nations - tourism has come to the forefront. It is now considered so important that universities and institutes are offering tourism studies. Tourism is an emerging industry in Arab oil-producing nations, and departments, ministries and institutions have been established to develop this vital sector.

In Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq and Syria, religious tourism is a guaranteed source of income that needs no promotion. Instead, the focus is on improving transportation and lodging. These countries have realised that they have other potentially profitable attractions that would contribute to GDP and promote development and modernisation.

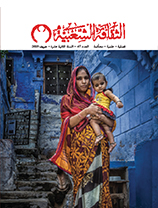

When creating their tourism promotion plans and borrowing from the tourism programs and activities of developed countries that cater to international tourists, the Arab Gulf countries discovered that the most important attractions in each country are based on the country’s cultural achievements throughout history. They chose to showcase what remains of their tangible and intangible heritage to attract foreign tourists.

Due to looting, many relics were removed and sent to foreign museums, but archaeological sites remain in Morocco, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and other Arab countries. These are widely visited attractions that need no governmental promotion. So, other than archaeological sites, what attractions are there for tourists?

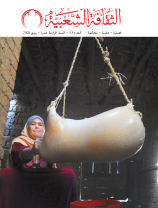

The experience of friendly countries in Asia and Eastern and Western Europe could be used as a model for intangible heritage-based tourist attractions. Such attractions could include songs, folkdances, costumes and explanations of customs and traditions. Spanish flamenco, Scottish bagpipes and Asian masked dances are now recognised throughout the world.

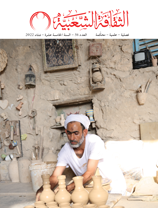

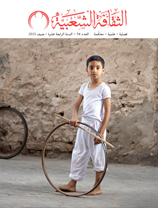

The plans in all Arab countries include folk culture elements such as songs, dances, costumes and traditional crafts. Though this trend is undoubtedly positive, many of these elements have been presented in a casual fashion that has distorted them and diluted their values, morals and aesthetics. In other instances, folk culture may need to be presented to tourists with a description of its background and meaning.

In our Arab countries today, folk troupes face a grave threat when their performers die without leaving any notes. Although these troupes help to encourage tourism, they are usually treated badly by event organisers and others who profit from their performances because these people are ignorant of the troupes’ significance. Realising the danger of this issue, countries signed UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention. Although the Arab countries signed the Convention, they’ve failed to observe it.

Another threat is that most folk arts are presented on tourism-related programmes or on official occasions. These are broadcast on satellite channels, and the audience sees only these ‘artificial’ performances.

In my opinion, we must return to our main concern, which is the need to collect, record, document and preserve elements of folk culture. Once these steps have been taken, folk culture can be used to attract tourists.

Ali Abdulla Khalifa

Editor In Chief