The Call for Rain in Imazighen (Berber) Rituals and Legends in North Africa

Issue 14

Mohammad Usus (Morocco)

Taghonja or ‘rain’s bride’ is a ritual widely known in Northern Africa, in both Arabic and Tamazight-speaking areas. One of the oldest rituals for calling for rain, rain’s bride (also Anzar’s bride) is an appeal to the heavens to send rain to lands threatened by drought, water scarcity and crop damage.

The ritual is performed throughout the Maghreb, with very slight variances among regions according to Emile Laoust, a well-known scholar who studied the Imazighen; a significant part of his valuable book ‘Mots et choses berbères’ describes Tagnja or Taghonja rituals across the countries and tribes of North Africa.

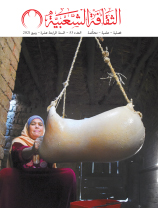

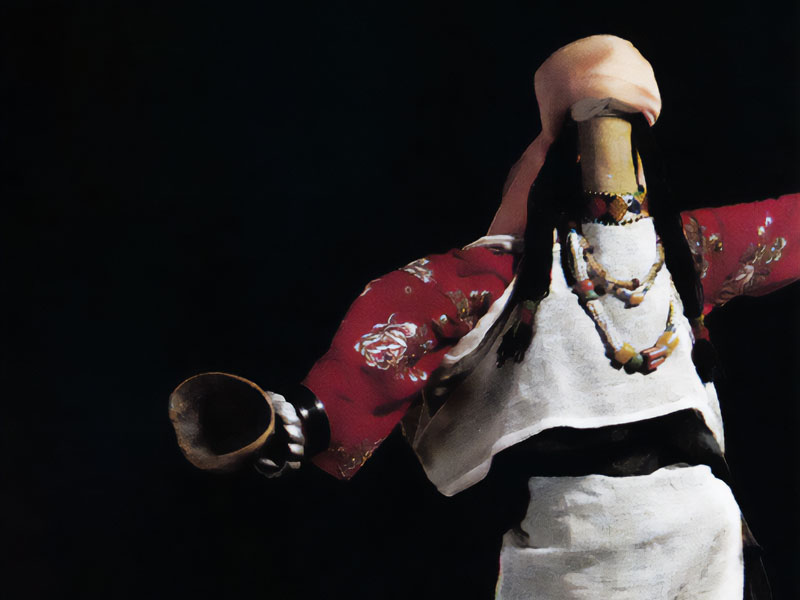

In the Anzar’s bride ritual, Tagnja or Taghonja is the name given to a wooden doll made out of a pestle or ladle and dressed in bridal wear known as Tislit. The doll’s arms are spoons that are meant to collect rainwater. Women carry Anzar’s bride across districts and villages and to shrines while chanting the prayers for rain. Children accompany the women, and people along the way spray the doll with water. A ritual feast is served near the river, on the threshing floor, in a shrine, or on top of a hill, according to the region. The doll, its name, its bridal clothes and the songs that are chanted may vary from place to place.

Sometimes women carry an unclothed ladle or large spoon during the procession, (as is the case in Jerba in Tunis and Mizab in Algeria), but the doll is always called some variant of the name Tagnja, such as Ghanja, Taghonja or Tarenza.

Most of the researchers who studied this ritual provided descriptive data without mentioning the ritual’s mythological origin, but H. Genevois collected a text from the At Ziki of High Sebaou (Kabylie) that includes an important story narrated by the Algerian tribe.

The old Amazigh and North African beliefs and mythology are entrenched in Maghreb in the people’s behavior, rituals, customs and language; they persist in the collective unconscious, even if forgotten.

Islam has greatly influenced culture in Maghreb, but the Amazigh people are still influenced by ancient mythology that has its origins in Ancient Mediterranean culture and traditions. As a result, it is impossible to understand the behavior and attitudes of contemporary Maghreb without referring to the mythology that underpins them. The collection, documentation and analysis of further details of this mythology would help to shed light on many of the Berbers’ secrets, beliefs, rituals and traditions, and on many aspects of both Berber and Arab Maghreb culture. A study of Amazigh mythology would help to explain the symbols and motifs in their rituals, tattoos, woven fabrics, ceremonies, traditional songs and poems.

Although the majority of texts about Imazighen mythology have been lost or altered, the rituals have survived. However, it is difficult to interpret a ritual without referring to its mythological origin because in many cases the ritual is merely a re-enactment and celebration of the myth. According to Gusdorf, rituals revive the myth and, according to van der Leeuw, the rituals are reincarnations of the myth.