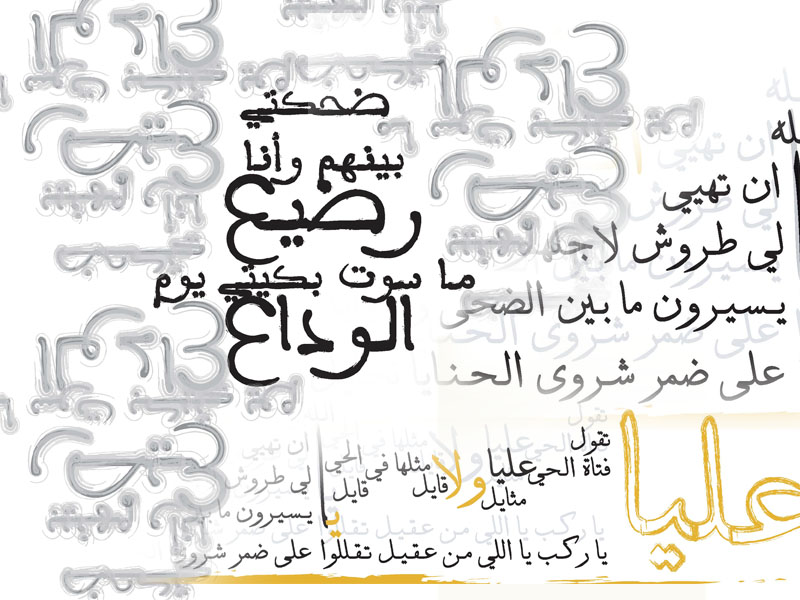

Nabati Poetry In the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf From the Poet of the Clan to the Poet of the Million

Issue 1

Ali Abdulla Khalifa

This article sheds light on the commencement of Nabati poetry. It is commonly held that folklore poetry is composed by laymen intuitively and impromptu to express their real experiences which mirror their psychological make-up and the collective spirit of lower-class people. This may apply to all types of folklore literature in the Arabian Gulf except one unique genre on which the few scholars who study it have differed in classifying it as such since most of its composers are known.

This genre is Nabati poetry; most of its masterpieces have been created by all social classes in the Arabian Peninsula, including the poor layman and the emir. And although the elite usually refrain from practicing the creative arts of laymen to keep themselves aloof from all laymen’s practices, they nevertheless practice this art which is considered a source of pride and for whose poets they hold a great esteem. Therefore, Nabati poetry reflects many aspects of people’s life and the social environment of the Arabian Peninsula which lends itself to investigation. A lot of poets have excelled in this art and a lot of people have learnt it by heart and narrated it. No wonder that it has such a great impression and impact on people and the entire life in this region. Its influence has been so immense that a poem may spark war such as the poem entitled ‘al-khuluuj’, meaning ‘the camel that lost its son’ by Abdulla al-’Uweini, who died in 1342 Hijra. Some poems are still considered a reference for historic events and bear witness to heroic deeds.

In this article, the author sums up the status and influence of Nabati poetry in this region which is equivalent to that of al-Jahili poetry and its impact on Arabic literature. He also focuses on the rhythmic patterns and meters of the Nabati poem which in its infancy adopted those of al-fusha (classical poem), while having their own syntactic rules not because the pioneer Nabati poets adopted al-Khalil bin Ahmad’s meters but because the Bedouin environment where those meters cropped up was the same environment in which this genre grew.

The article also points out the relationship between Nabati poetry and singing. In fact, this type of poetry was often composed to be sung accompanied by rubaba (a musical instrument with strings) in divans and rulers’ palaces or in public yards as pail of preparations for war or on horse or camel back. The author discusses the types of Nabati poetry and its development by famous poets like Muhsin al-Hazzani, Muhammad bin La’boon, and Abdulla Faraj who devised new rules and diverse rhymes for the Nabati poem. This made this type of poetry common not only in the desert but in the city as well.

Furthermore, the poet asserts the importance of documenting and publishing Nabati poetry a lot of which has been lost and some has been distorted. He criticizes the role of modern media which introduce this type of poetry to the new generation in the same way as it used to be introduced to Bedouin tents and divans five centuries ago, a style which is a far cry from the spirit of modern times, which has in turn, rendered it unintelligible to most people today.